In simple terms, bird ringing involves putting a small metal ring on a bird’s leg. Each ring has a unique number meaning, once a bird has a ring fitted, it is identifiable as an individual and, if recaptured or found, we can learn about the its life – where it goes, how long it lives etc.

Obviously birds, and particularly small birds, are very delicate so the process of catching and ringing them needs to be done very carefully. In the U.K. bird ringing is very strictly regulated. Without a permit it is illegal to handle a wild bird unless it is for the bird’s welfare – for example, because it is injured or trapped.

Permits for bird ringing are issued by the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) and anyone who wants to become a bird ringer has to undergo several years of training under the supervision of a fully qualified and experienced ringing trainer. The bird’s welfare is always paramount and great care is taken to ensure ringing activities are safe. Most bird ringers in this country are amateur volunteers who fund their activities themselves. They are still expected to maintain the same high standards as they would if they were professionals.

All the data collected by ringers across the nation is entered onto a central online database enabling the information gathered to be used to study lives of birds. Around a million birds are ringed in the U.K. each year.

The rings that are fitted are very small (roughly equivalent to us wearing a small wrist watch or bracelet) and are carefully fitted to ensure they do not harm the birds. If you ever find a dead bird with a ring, it is well worth reporting the number as this will tell you something about the bird’s life history and add to the database.

Bird ringing has been around for well over a century and, historically, unlocked many of the mysteries about the birds that populate our lives and the seasons. For example, before ringing demonstrated that swallows which summer and breed in the U.K. winter in southern Africa it was thought they wintered by burrowing into reed beds and hibernating. When you think about it, in many ways, this makes more sense than a tiny bird weighting less than an ounce migrating half way around the world and back!

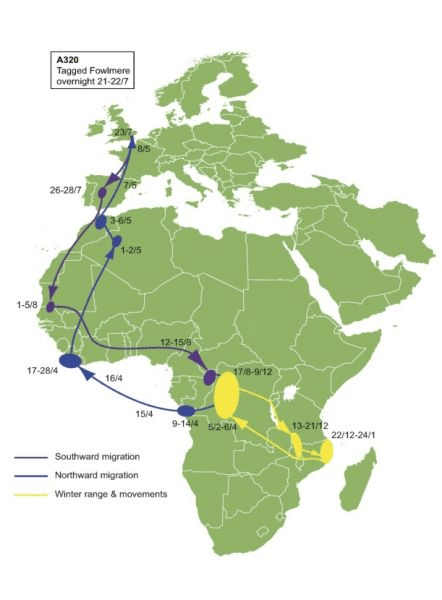

In more recent years, tracking devices of various kinds have gone much further in revealing the amazing journeys that our migratory birds undertake. Bird ringing will only ever reveal a few moments in a bird’s life – when it is initially ringed and then when it is subsequently recaptured or found. Tracking can follow the bird’s progress on a daily or even hourly basis showing not only where it goes but what route it takes, where it stops off to feed on the way etc. etc.

However, tracking devices are expensive costing hundreds if not thousands of pounds each whereas rings cost pence each. So trackers can only ever be fitted to a few birds whereas rings can be fitted to many. In recent years the emphasis on bird ringing as moved to some extent away from unlocking the secrets of migration to the monitoring of population dynamics – how long birds live, how many young they produce etc. – and how this is changing with time. This is extremely valuable information for conservation as it can help, for example, reveal the factors causing some bird species to suffer major declines in population.

I have been a bird ringer on and off for over 40 years and am well aware of the valuable data bird ringing can produce. One of my aims in trying to make North Nibley into a swift hub is to collect data on the lives of our swifts by ringing them. Only by this means can we know whether the same birds are nesting in the same box each year, how many of the young raised return to the village etc. Currently, very little of this data is being collected for swifts so the information gathered could be of great value in working out how to protect and encourage the threatened population of these birds.

Swifts are very sensitive to disturbance in the nest so ringing has to be done with great care. However, there are national guidelines on how and when it can be done safely which I strictly follow – the birds’ welfare is always paramount.

So, if you have swift boxes fitted to your house, I will be monitoring your birds by ringing the young and catching the adults each year so that, over a period of years, you will start to get an insight into the lives of your swifts.